Growing Up With Sharon Stone In India Of The 90s

The clueless internet generation would never know what it meant to grow up with Sharon Stone in India of the 90s

by Sayantan Ghosh

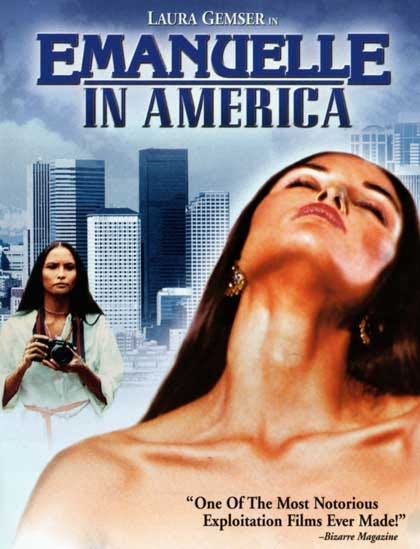

I t all started one sultry moist afternoon in (then) Calcutta when by a simple twist of fate I knocked on the wrong door of my classmate’s elder brother’s room instead of his. I was invited to Moinak’s place for a rather customary session of Nintendo video games but landed up in Mihir’s room, who was in the 10th standard at that time. Mihir and three of his friends had just inserted the VHS tape of Emanuelle in America into the player then. Throwing me out of the room would have raised suspicion, and thus began my somewhat morbid love-and-hate relationship with porn.

Growing up in the late-80s and early-90s was not just a 20-year separation from the young people of today. Even the revolutionary ‘opening up’ of the economy in 1991 by the Narasimha Rao government couldn’t bridge the gap that existed between us and our future flag-bearers. The biggest truth is that we didn’t have the internet. And a little later when the ancient VSNL modem came into our lives; then honked, stomped and kick-started with that visceral noise, it ended up waking the whole neighborhood from their sleep.

In the mid-90s, every young lad with a cricket bat in hand wanted to be Tendulkar or Jadeja. One day when Sanjay came to the field carrying an unsuspecting pencil-thin Hindi book in his hand, I was practicing my cover-drive for the Sunday match against a rival club. Sanjay walked up to me and informed that he had managed to whisk away the copy from his NRI-uncle’s duffle bag and even offered a sneak-peek if I traded with him my opener’s position in the game on Sunday. I agreed.

We spent the rest of the afternoon sitting on the terrace of Sanjay’s house, munching on cheap candies as he read out the story of an incredibly thirsty woman who stopped by a local garage beside a highway for a quaff. I was about 11 then and remember paying careful attention to every word, trying to imagine the whole sequence down to the minutest detail as described by the author. It turned out that the wispy paperback wasn’t the entire book, but rather only a part of it which Sanjay had managed to tear off from the original. By the time the air jack and power driller innuendos got over, we had already reached the last page in our possession. In 2015, it wouldn’t take more than a minute to find out the name and history of this particular book, or where it is being sold or maybe the entire story too! Thanks to Google. But in 1997, two teenage boys on the verge of extreme physiological transformation walked off to their homes with a fertile imagination but disdained hearts.

But before this gigantic wireless explosion of interconnected networks happened, it all used to be hard work. Like good television, adult cinema also brought people together.

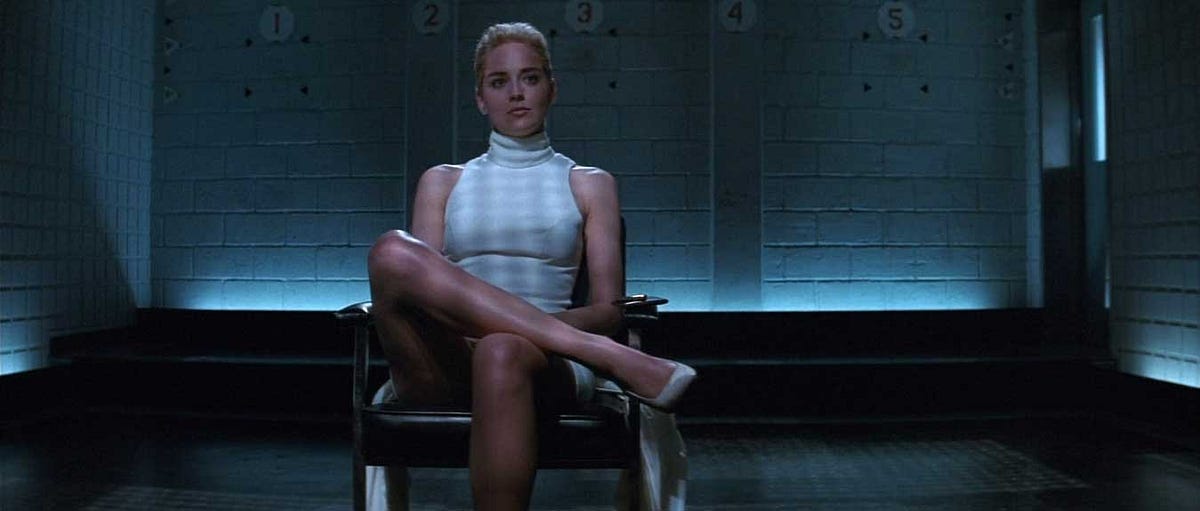

People say that with time everything changes. Perhaps this aphorism is true for everything except a man’s growing libido. Otherwise there’s no reason why two years later from that ill-fated day in ’97, I would find myself stuck with Sanjay again inside the dingy by-lanes of Chandni Chowk, with a deadly Kalboishakhi (storm) brewing right above our heads, a frequent visitor during the month of April in Bengal. We were searching for the uncut version of Sharon Stone’s Basic Instinct in the gullies of old Calcutta, where apparently one used to get every electronic item that was either unavailable in the rest of the country, or sometimes even unheard of. Now these were days when Sunny Leone was not generously offering slices from her life on free download forums and most men, young and old both, had to be satisfied with the regular dose of “assamese” and “mallu” imports. These we later discovered were generic names practically given to any tape that was produced and shot in India with overweight Indian men and women. Amid this frenzy, Sharon Stone was a goddess. And Basic Instinct, her 1992 film with the infamous “leg-crossed” scene, was a gift sent straight from the heavens. When the cable TV version edited out most of the much-awaited scenes, Sanjay took up the charge of finding out the unedited film from even the deepest corners of hell. I was chosen to be his Watson for the particular feat.

After more than an hour of visiting every pirated-disc vendor and returning empty-handed, we sat down at a tea stall sipping from our bhaars, waiting for the rain to stop. When suddenly from nowhere I felt an elderly hand touch my back who then asked me to walk with him. I looked at Sanjay’s face and saw he was already paying for the tea by then. The old man definitely had earned our curiosity. We walked behind him for about 500 metres through the mud-spattered pavement of Chittaranjan Avenue until we reached a rundown old building that must have been gathering dust since the British had left India. He opened a small door right next to the main entrance and walked down a flight of stairs. Both Sanjay and I had started suspecting his sinister motives by then; after all, we were middle-class Bengali boys who had grown up hearing stories of how if we followed strangers into dark alleys we would be kidnapped, blinded or dismembered and left on the streets to beg. Graphic details and terrifying tales of monstrous men and poltergeists was always the forte of most east Indian grandmothers. Yet so resilient was the urge of witnessing Sharon part her bountiful legs while several police officers questioned and sweated profusely around her, that our feet trampled along with him silently. At the bottom of the wishing well awaited us a depository of incredible wealth. Stacked inside enormous sacks, otherwise used for storing food grains, was outlandish pornographic talent from all around the world.

The same year, one middle-aged unemployed man ironically named Shaheb, who used to live in our colony opened his own CD-parlor in a minuscule 6x6 cubicle near our playground. When excitedly some of us decided to pay him a visit one evening, he briskly boasted about his entire collection of popular Hollywood hits and award-winning films at first. Then he shook our hands and whispered in our ears, these very words: “Remember, I am a businessman first and your uncle later. Don’t hesitate to ask for anything, I can even change the covers so that you can take any disc to your homes without any risk.” Welcoming and kind as the gesture was, we all felt slightly weirded out that day. But it broke some sort of ice between five young boys and a struggling young man who was only trying to do his job well. We never rented anything barely +18 from his store, but often on cloudy evenings we sat together over tea and vegetable chops, talking films and cricket, the two things that drives India.

Pornography has this quality. It bridges superfluous gaps of age, gender, caste and hierarchy. Whether it was trading a borrowed Penthouse with a stolen Playboy discreetly with senior boys in school or exchanging candid glances with the new girl on discovering a copy of the Kama Sutra hidden underneath the Maths teacher’s notebook in tuition class. Today everything happens behind closed doors. Everybody has a tablet or a mobile phone, every content is floating in the air outside your window waiting to be grabbed, everything is public. But before this gigantic wireless explosion of interconnected networks happened, it all used to be hard work. Like good television, adult cinema also brought people together. Young boys and girls explored their sexualities without downloading an app and the art of acquiring the content with assistance from countless acquaintances took precedence and made for great stories. A year ago, I went to Calcutta and decided to pay good old Shaheb kaka’s CD shop a visit. Someone in the colony told me that he had an unsuccessful eye operation last year and since then could recognize very few faces.

I didn’t introduce myself, and behaved as any general customer in his shop would, inquiring about the latest blockbusters and acclaimed regional films, if any. He answered all my questions with a familiar enthusiasm. A little later, just to be cheeky, I asked him if he had any porn in his stock. At jet-speed he brought out a register from underneath his desk and began to show me a list of X-rated titles. There was a sweet melancholia in his voice, like someone had asked him about a long-lost friend. “Nobody rents these anymore,” he said sadly while adjusting his spectacles. “Everyone downloads what they want, even the wage laborers. But there was a time when we considered this as no less than any other form of cinema. At least nobody’s throat gets slayed in these for better ratings.” I didn’t disclose my identity to him that day, I don’t know why. His store, like several others in the city, which used to be the central source of the entire locality’s weekend entertainment, was clearly struggling and on the verge of shutting down. But before I left, what possibly was the last time I saw ‘Star Movie Parlor’ in business, I asked him to lend me the CD of his all-time favorite adult film. Shaheb kaka smiled mischievously, asked me to wait for a little and went inside his store room through a back door. A minute or two later he came back and handed me a copy of Emanuelle in America, its cover changed with a popular Hindi film’s over-the-top poster.

Also read

Tangles of Leftover Hair

by Rini Barman ¶

It is 5.30pm, Tuesday. Just took a shower.medium.com