Rape and Revenge, As It Happens In B-Grade Films

I started watching what is often termed as B-grade cinema in my adolescence. Hormones, of course, and the little bit of independence that parents granted at that age made it easy to judge for oneself, finally, the much heard of titillating mystery that such films supposedly offered.

In those days, at least in small towns like the one which I grew up in, even respectable cinema halls played a B-grade film in the morning show. The posters uniformly featured buxom girls in very skimpy clothes, in one or another variation of a come-hither pose. There were men too sometimes, but they did not really matter. The story lines mostly revolved around ghosts, who were often women, who had been wronged in some way or the another, mostly raped and killed. They became witches or chudails and avenged the loss of their honour by hooking up with the villains and killing them. Of course, there were other type of B-grade films, acted in by Mithun Chakraborty mainly, but they were often pale imitations of the standard mainstream Bollywood fare. Yet another variety of B-grade films had nothing to do with what is termed as the rape-and-revenge trope and was simply an excuse for sleaze.

Essentially, B-grade cinema attracts derision. Sometimes in a funny way. The so-bad-it-is-good variety. But its status is unequivocally established. It is not shown in the fancier cinema halls. Respectable people do not want to be caught seeing it. It is considered seedy, aiming at rousing the baser feelings.

B-grade cinema, then, with its abrupt screenplays which focus more on the kicks than narrative rigor, seems the actual inheritor of the rural folk performing arts tradition of the country, though in a kitschy way. In fact, sexual ribaldry is also not alien to several of these traditions. In a way, for a population deprived of its usual entertainment by virtue of living in cities for economic reasons, B-grade cinema fulfills that need.

Simply speaking, mainstream films stand for reason and rationality whereas B-grade cinema embraces irrationality and intuition, as opposed to reason. It is on this fundamental difference that their different identities and existence rests. For example, if we examine the trope of the avenging female, even the femme fatale, and especially the witch or chudail, a staple of Indian B-grade cinema, the difference manifests itself very clearly.

The woman, whose menstrual cycles are supposed to coincide with the moon — a common shorthand for madness, lunatic and lunar share the same Latin root — represents irrationality in the patriarchal world we live in. It is the man who holds the reins to reason. Other factors like the mythologised whimsical nature of women also add to her supposed irrationality.

In her remarkable essay in the 2008 issue of Granta on “Fathers”, Siri Hustvedt, citing the anthropologist Mary Douglas, says that the two kinds of power that exist in our male -dominated culture are one that exercises legitimate articulated authority inside a known social structure and one which is implicit, unarticulated and unknown. “She points out that the witch is a perfect example of a threatening counter-power, one that is not part of a culture’s explicit architecture,” writes Hustvedt.In that sense, B-grade cinema allows that counter-power to threaten the patriarchal culture’s “explicit architecture”, a possibility that mainstream cinema, the upholder of its status-quo — as demonstrated by Laura Mulvey in her seminal essay Narrative Cinema and Visual Pleasure- denies. When the super natural is added, the irrational element becomes starker.

By accommodating the trope of the avenging female, it gives agency to the wronged woman and thereby subverts the mainstream discourse where law, the codified form of state rationality which represents the masculine, or a brother or lover dispenses justice. It is indeed true that the trope has permeated the mainstream since the boundaries between mainstream and B-grade remains porous, depending on sociological factors, although delving into its various aspects is out of the scope of this essay.

The prevalence of super natural — thus irrational — themes and greater role for avenging females, among other factors, demonstrate that B-grade cinema is where the society allows the inarticulate, dark, female power that it suppresses to assume significance to a certain extent. However, since such films are mostly enjoyed by a largely male audience, and are produced by men too, the limits of female agency are curtailed and complicated further.

II

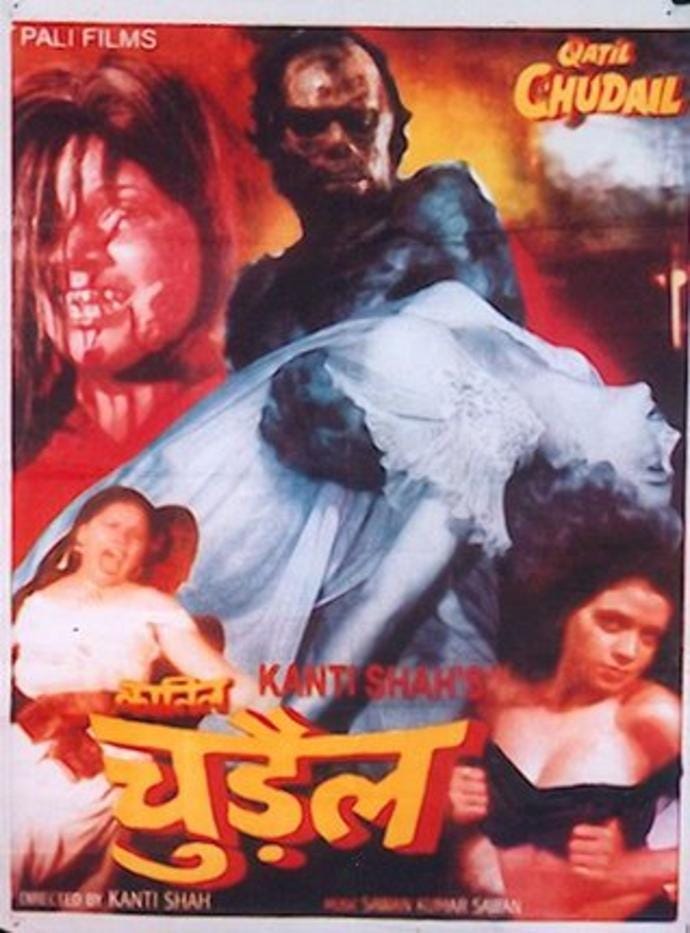

For the purpose of this essay, I saw three films belonging to the genre: Qatil Chudail, Chudail No 1 and Chandani Bani Chudail.

All the three films have a witch figure who is wronged by men and who avenges the loss of her honour and/or death at their hands. However, the films make subtle adjustments to the tropes which are revealing.

In Qatil Chudail, for instance, the girl who becomes the witch after death does not get raped. However, she is punished for her sexuality by first her father and then her brother-in-law.

The film’s opening shots set up the theme. The girl studies at a college. Her father, who in one scene sits holding and caressing her hands a bit too intensely, wants to marry her off. However, she finds a lover of her choice.

One day, while she is making out with the lover at home, her father returns and finds her in what is euphemistically described as a “compromising position.”

Enraged, he proceeds to shoot down the lover. The girl, who is traumatised by the event, is sent to her elder sister’s place. It is pertinent to note that the girl herself is not killed by the father, who represents the patriarchal nature of the society. His killing of her lover presents the possibility of his jealousy getting the better of him. At the same time, it denotes his anxiety at the girl- whose mother is absent, thus implying she was brought up by the father — taking an interest in exploring her sexuality for which he punishes her. The subtext here is of incest, which is a taboo because of its subversive aspect. Incest as taboo is a necessary pre-condition of the rationalisation of desire.

At her sister’s place, the girl is unable to get over her trauma. She imagines the servant for her deceased lover — whose death she has not been able to come to terms with– and is caught seducing him by her brother-in-law. He warns her off it. However, the girl repeats the same — tries to seduce him which he seems to enjoy initially — with him a few days later following which he guns her down.

Along with incest, the reactions of the father and brother-in-law who is sheltering her,both patriarchal figures, to her sexual escapades denote typical patriarchal reactions. “Unbridled” female sexuality causes discomfiture, causes cracks in the careful constructs that a patriarchal society follows. Slut-shaming, whose apogee is honour-killing, is part of its brutal defence.

Although the girl in this film is not raped and killed afterwards, she is indeed punished for exploring her sexuality and for breaching the patriarchal norms defined for doing so. Hence, it still complies with the over-all structure and narrative of such films. Technically, the girl’s murder is an instance of honour-killing and it suits the Indian milieu. Western rape-and-revenge movies do not contain this aspect, as far as I know.

Following her death, the girl begins to inhabit a Haveli after killing people living there — a family of Thakurs, another potent symbol of patriarchy — and others who visit it afterwards.

In Chudail No 1, the trope is more or less maintained but with a twist. The story line is classic B-grade. A gangster called “Master” is after the life of a CBI officer who has a file on his deeds. Unable to get it from him, he gets him and one of his daughters killed by his henchmen who first rape her.

While in Qatil Chudail we do not get to see any examples of male figures with redeeming qualities, except the slain lover killed without any real fault who has a small part, Chudail No 1 emphasises the role of the police officer, who is married to the other daughter, as an honest officer. In another interesting indianisation of the trope, the girls are identical twins. The police officer suspects his own wife of the murders of the henchmen till he realises the truth at the end.

In his insightful essay, “Don’t Blame This On A Girl”, anthologised in Screening The Male: Exploring Masculinities in Hollywood Cinema, Peter Lehman has gone into this aspect of representation of men in such films. He states that the more extreme films in the genre, like I Spit On Your Grave, contain no representation of any man with redeeming qualities, not even cops investigating the case.

However, in all these three films, we at least have cops investigating the crime, though in Qatil Chudail, they appear very late. But in Chudail No 1, the cop investigating the crime plays parallel lead to the witch figure, thus reinstating the balance somewhat. The twist, however, in Chudail No 1 is that the father also avenges his own death and the rape and murder of the daughter along with her, turning into a ghost himself.

This allies with the analysis of Lehman that ultimately, it is the fulfilment of male desire that is aimed at in these films — the desire for an expression of their repressed homosexual fantasies — which he compares with boxing. Along with that, he also posits the possibility of fulfillment of masochistic desires, in the classic tradition of Venus in Furs.

The homo-erotic element is almost always present in such films, as the rape which starts all is usually committed by a group of friends. It happens in both Chudail No 1 and Chandani Bani Chudail. In Qatil Chudail also, the witch kills male members of a Thakur family first and later, a group of petty criminals.

Like in western films of the genre, here too, the very sight of male sexuality appears to disgust the witch figure. Killings often occur while the males are engaged in coitus, or before or after the act. It appears that the films must show the male victims of the witch to be sexually functional. Also, many victims are lured by the witch figure, who takes on an enticing form.

However, one crucial difference seems to stand out. Interestingly, in all the three films under review, the witch figure had a female alter-ego, so to say. In Qatil Chudail, the witch figure has a twin, who is far removed from her sister’s machinations and who exorcises her ghost in the end by killing her with a charmed trident. In Chudail No. 1, the twin sister of the witch is shown to be extremely obedient and domesticated house-wife and she is finally exonerated from suspicion when her husband realises the truth.

Chandani Bani Chudail also inverts the tropes a bit. In this film, there are clear demarcations of a good girl and a bad girl. Chandani is the good girl whereas her friend Madhu is the bad girl, who flirts with boys and goes home late, making the excuse of “extra classes.” While Chandani initially defends her friend, she ends up informing Madhu’s family about her activities. When Madhu finds out that Chandani snitched on her, she invites her to a party, where her male friends rape her and thinking her to be dead, throw her in the ocean.

However, Chandani does not die. Making use of everyone thinking her to be dead, she goes about her revenge in the garb of a witch, thus demonstrating a diegetic self-consciousness of the genre on the part of the film-makers. In the end, Chandani’s true identity gets revealed to the police but she is not shown to be arrested or punished.

In conclusion, it may be reiterated that Lehman appears to be correct in analysing such films to fulfil male desires related to masochism, and homo-sexuality: “It may be the unique function of the female rape-revenge genre to disguise the homosexuality by having a beautiful woman brutally attack the male body in general and the genitals in specific.”

However, it is my contention that employing what Hustvedt writes, these films also allow for an expression of the unarticulated, irrational, implicit counter-power of female sexuality that threatens the “explicit architecture” of patriarchy.

It must be noted that while in one of the films, the ghost is exorcised, in the other one, the witch just walks into the night with the father. At the same time, in the third film, the girl who kills her rapists by pretending to be a witch is let off by the policeman. Thus, there is a subversion of the rational and moral code of mainstream cinema.

As far as the representation of rape itself is concerned, in both the films, it was hardly shown. I have seen much more titillating presentations in mainstream Bollywood cinema. However, there was some sleaze but in other forms.

Over-all, the very possibility of a woman taking the business of revenge in her own hand — Kill Bill draws on the western variety of such films and its director is a well-known aficionado of B-grade films — has a subversive aspect about it that mainstream cinema usually denies. Bu turning the avenging female into a witch, another supposedly irrational element gets added which, while strengthening the figure also allows for a staunchly patriarchal society to dismiss it more easily. It is in this paradox that the avenging witch figure of Indian B-grade cinema can be located and analysed.

Of course, this time I could only see the films on YouTube. It was easily accessible and there was no one to stop me from indulging. However, the thrill of missing school, and risk of possibly ignominious discovery was sorely missed.