Shakespeare is Wrong, the Blind do not see Darkness: Borges on Blindness

Contrary to what we believe, Borges tells us that it isn’t the darkness that bothers the blind.

Those who are aware of the Hamburg based Dialogue Social Enterprise’s Dialogue in the Dark experiments would know that it is intriguing to say the least.

Initiated by Andreas Heinecke, a German journalist and documentary filmmaker, witness to both sides of fascist Germany — -his mother’s family being at the suffering end of the holocaust and his father’s family being Nazi supporters — -the experiment was devised to test our tolerance for otherness. It was to put the perceived superior of the people in the shoes of the “other” and test their strengths, if there were any, that allowed them that feeling of superiority.

Since 1988 they have conducted a number of experiments across the globe that intend to blur and merge the worlds of the blind and the sighted with this same vision as explained on their website:

In Dialogue in the Dark exhibitions, visitors are led by blind guides through a specially constructed and completely darkened space. Conveying the characteristics of a familiar environment such as a park, a street or a bar, a daily routine turns into a new experience. A reversal of roles is created as sighted people are torn from the familiar, losing the sense they rely on most — their sight. Blind people guide them, providing security while transmitting a world without pictures.

The experiment in its concept is remarkable, an equalizer because it necessitates that both party depend on their “available” senses. But in those moments do the worlds visible to both parties look the same? If not, whose dialogue is it with the “dark”. Is darkness a state that the blind live in? Is black the colour they can see? Are their struggles against a colour that we regularly associate with abyss where everything falls and dissolves to the point of unknown?

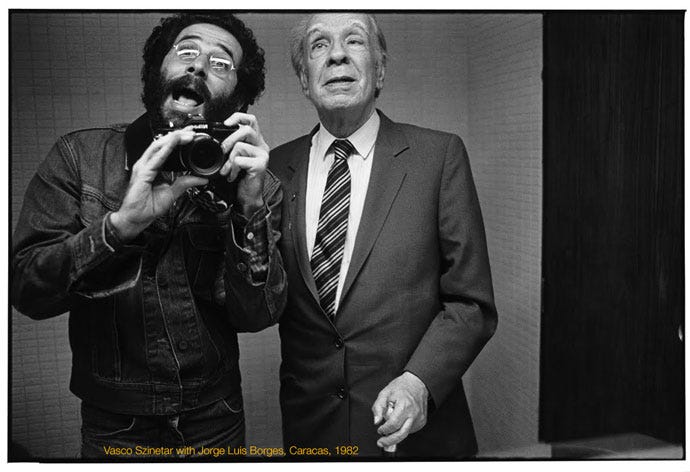

Shakespeare, like many of us, perhaps believed so when he wrote, “Looking on darkness which the blind do see”. But Jorge Luis Borges who lived a little more than three decades of his later life in partial blindness did not see so.

People generally imagine the blind as enclosed in a black world. There is, for example, Shakespeare’s line: “Looking on darkness which the blind do see.” If we understand “darkness” as “blackness,” then Shakespeare is wrong.

There was a visible change in Borges the person post his blindness. As Eliot Weinberger tells us in an introductory essay to Selected Non-fictions:

Before his blindness, Borges was so shy that, on the few occasions when he was asked to lecture, he sat on the stage while someone else read the text. In his last three decades, however, as his star rose and he was invited all over the world, he evolved a new form that is still misleadingly given the old label “lecture.” Closer perhaps to performance art, these were spontaneous monologues on given subjects. Relaxed and conversational, necessarily less perfect than the written essays, the lectures are, like the prologues, a particularly Borgesian subgenre and delight.

Borges was aware of his imminent blindness from the disease that had consumed three generations of his father’s. It was progressive blindness. He did not wake up suddenly and realize that he has lost his sight. He equated it with a slow nightfall that going towards its happening that rendered him “modestly blind”, modest because he was totally blind in one eye and only partially in another.

Contrary to what we believe, Borges tells us that it isn’t the darkness that bothers the blind. It is instead the same colours again and again that makes one crave for the comfort of black.

One of the colors that the blind — or at least this blind man — do not see is black; another is red. Le rouge et le nair are the colors denied us. I, who was accustomed to sleeping in total darkness, was bothered for a long time at having to sleep in this world of mist, in the greenish or bluish mist, vaguely luminous, which is the world of the blind. I wanted to lie down in darkness. The world of the blind is not the night that people imagine. (I should say that I am speaking for myself, and for my father and my grandmother, who both died blind — -blind, laughing, and brave, as I also hope to die. They inherited many things — -blindness, for example — -but one does not inherit courage. I know that they were brave.)

There’s blue and green that he could still see and yellow in particular remained loyal to him, bringing back memories of childhood where standing in front of the tiger’s cage in a zoo he would marvel at the gold and black of the animal, the latter of the colours he could only chase post his blindness — -this chase is visible in Borges’ poems “The Other Tiger” and “The Gold of the Tigers”.

But black apart, there was another colour Borges dearly missed. So much so that he would decide undergo treatment just to be able to see that again.

The blind live in a world that is inconvenient, an undefined world from which certain colors emerge: for me, yellow, blue (except that the blue may be green), and green (except that the green may be blue). White has disappeared, or is confused with grey. As for red, it has vanished completely. But I hope some day — -I am following a treatment — -to improve and to be able to see that great color, that color which shines in poetry, and which has so many beautiful names in many languages. Think of scharlach in German, scarlet in English, escarlata in Spanish, ecarlate in French. Words that are worthy of that great color. In contrast, amarillo, yellow, sounds weak in Spanish; in English it seems more like yellow. I think that in Old Spanish it was amariello.

Blindness changed Borges’s approach to his art. Since he never learned braille, he lost his ability to read. He depended on his memory to recollect sonnets and memorize poems that he would later dictate. Borges was scared that that was the end of Borges the writer and Borges the reader, as he revealed in an interview to the New York Times in 1971.

When I lost my sight I was rather worried over it, and in my dreams I was always reading. Then somehow I never could read because a word became twice or thrice as long as it was, or rather instead of one line there would be other lines springing like branches out of it. Now I no longer dream of reading, because I know that’s beyond me.

Sometimes I see a closed book and then I say, ‘I could read this particular book,’ but at the same time even inside my dream I know I can’t, so I take good care not to open that particular book.

Was it a coincidence that Borges became the director of the National Library of Argentina at the end of the very same year when he went blind? Was it a coincidence that he inherited the legacy of two more blind directors before him?

Borges pondered upon those questions and then wrote in the “Poem of the Gifts”, unsure whether he or Paul Groussac, his illustrious blind predecessor, had written it:

No one should read self-pity or reproach

into this statement of the majesty

of God; who with such splendid irony

granted me books and blindness at one touch.

You can buy Borges’s Selected Non-Fictions from here

You might also like

I.S. Johar on Sexual Repression, Homosexuality, Incest and Sex with Gods

If you google I.S. Johar’s name with the auto-suggest feature on, it asks you to go ahead with “is johar and yash johar…medium.com